[layerslider id="13"]

Sangachok is one of the villages severely

affected by the Nepal earthquake.

It started the year with 2,000 houses.

Now, it has just 200.

For the Christian community here, as elsewhere in Nepal,

Christmas was very different this year.

Christmas story main text 1

On Christmas day, at 10:30am, Pastor Kumar Pokharel stood by the zinc structure that was his makeshift church, draping pink flower garlands across the entrance. He had a busy day ahead. In a little while, his small congregation would trickle in, some of them arriving after more than an hour’s walk across narrow mountain trails, to fit under the arched, corrugated sheets that made up this unusual church in the hilly district of Sindhupalchowk for the most important service of the year.

“We are so happy that we are together for this service,” he said. “We are happy to be celebrating, and happy to have a shelter to celebrate.”

Pokharel, who wore light blue jeans and a hooded sweater, is 24 years old. This morning, he had walked 30 minutes from the small hamlet that stood in a remote woodland clearing in the valley to get here, to ensure everything was in order for the service and the Christmas feast that was to follow. For his parishioners, today was important. All of them, to the last person, were struggling to rebuild their lives after the April earthquake. Most had lost their houses; many, loved ones. Today was respite. A short pause in a long ordeal, an oasis after a summer of sorrow. The pastor was nervous. He wanted the day to go without a hitch.

“Christmas is a little bit different here,” Pokharel said. “More people are not coming because people have their own problems. They don’t have homes. But I am happy because those people who are coming, they can enjoy each other … celebrate Christmas together.”

Pastor Kumar Pokharel. Photo: Patrick Ward

The protestant congregation that Pokharel serves is about 80-strong and lives in and around Sangachok, a village 70 kilometres east of Kathmandu. You need to walk 10 minutes from the main road, across a path of mud, rocks and rubble to reach the church, which stands atop a hill, amid a hamlet of metal shacks, overlooking a magnificent valley. The original church had stood a few kilometres away, but was destroyed in April. Pokharel and his parishioners had rebuilt this one on donated land a few months later, arching zinc sheets and rigging it with wires for electricity.

Finishing the decorations, Pokharel walked over to where a dozen or so parishioners had gathered. They sat around a large tarpaulin, slicing cucumbers, chopping tomatoes, boiling potatoes. A young man in a leather jacket was stoking a small wood fire, while a teenage girl crushed spices in a stone bowl.

By late afternoon, the congregation had gathered in the church, with a crowd spilling out into the tent that had been erected just outside. Pokharel had by now changed into trousers, shirt, tie and waistcoat. He took to the stage at the back of the church, plugged in his electric guitar. Three other singers climbed on to the stage and as the group began to sing Nepali hymns, the congregation, sitting cross-legged on the ground, began to clap and sway and pray.

Christmas story main text 2

It has not been an easy year for Pokharel’s congregation. Sangachok falls under Sindhupalchok, the district most affected by the earthquake. Of the 8,702 people who lost their lives across Nepal in the earthquake, 3, 440 belong to Sindhupalchok. Some 90 per cent of houses in the district were either destroyed or damaged, and the scope of this devastation is remarkably evident in Sangachok. It began the year with more than 2,000 houses, but is ending it with just 200. Around 160 people are believed to have lost their lives.

I had been elsewhere in the district, in September. At that time, on seeing the temporary shelters, tents, and the piles of rubble still being cleared, I wrote it felt like the earthquake had struck just yesterday. That shocked me then, and on my return to the district now, I was hoping the situation would have improved, at least slightly. After all, the emergency relief phase of NGO operations was long over. Nepal’s new constitution had been passed, and the new parliament had finally established the National Reconstruction Authority, the organisation entrusted with mobilising the funds promised by international donors and overseeing the rebuilding.

But as my microbus pulled into Sangachok in the morning, the effects of the earthquake were instantly apparent. A huge mound of bricks and cement lay at the side of the road. The row of shops and houses that I walked past was punctuated with large gaps, like missing teeth, making way for a view of the valley. The mound of bricks and cement, it transpired, was the local school. Like nearly all schools in the district, this one collapsed on 25 April, which, being a Saturday, was closed. The school grounds were now being used to shelter survivors.

To understand the situation in the area, one must know a little of its breathtaking geography. Villages are spread across a series of hills here, and all around you can see the steep, tapered landscape of farmlands against a background of the majestic Himalayan mountain range. To get from one place to another here, you went on foot, across steep hillsides, carefully choosing footholds on rocky outcrops and solid earth.

As the cold morning air began to slowly give way to the powerful heat of the winter sun, Shrijana Baral (featured in the main video) arrived from the nearby village of Melamchi. Shrijana was a community radio journalist and a Christian. Like most people you meet in the district, she had lost her home and several family members in the quake. It is tragic, but that’s how it is here: when you meet someone from Sindhupalchok, you can almost take it for granted they have lost someone in the earthquake.

“This is a hard moment for us, but in this difficult moment we are trusting God,” she said. “Last year we celebrated our Christmas in a beautiful house, a beautiful home, but right now we are in a small and temporary home. It is not a fine situation for us, but we have to hide our sorrow, we have to hide our tears.”

Later, when I meet Pokharel, I ask him about the size of his congregation. It was difficult to put an exact figure to the number of Christians in the area. Some 50 parishioners were expected to the service, he said, though there were many more who were unable to come due to the various stresses the earthquake had inflicted on people’s lives. His flock was growing, he assured me, and maintaining a place of worship was central to that.

The pastor, like most of the people affected by the earthquake, was grateful for the presence of an outsider. Partly this was due to the friendly, welcoming nature of Nepali society, especially in the countryside. You are instantly made to feel like a guest of the highest importance. But it is also because people wanted the world to know about what they had gone—were going—through. There was a sense that they had been forgotten.

Christmas story main text 3

Many of those who came for the Christmas service were young children. Some had dressed in splendour. A group of little girls arrived, with eye make-up, wearing red and gold dresses imported from China. Sindhupalchok borders Tibet; it is closer to China than much of the country.

But not all children were well turned-out. Some came in ragged, earth-stained clothing. One such small boy sat with me during the service, one of the 1.7 million children across Nepal who has been affected by the earthquake according to a UNICEF estimate, reaching out to hold my hand and occasionally hug me.

“I work especially with the children,” the pastor was to tell me later. “They have psychological problems, physical problems. They need encouragement.”

There was a talent show after the service. The zinc church resonated with more music and singing, and even a spot of stand-up comedy. “This year’s celebrations are very different,” said Pokharel. “After the earthquake there were so many difficulties. We had no buildings, no temporary homes. Over the past year there have been no proper deliveries. We have problems rebuilding.”

He experienced his own personal sorrows in the year, losing his house as well as a loved one. “My grandfather died in the earthquake and my grandmother was injured,” he said. “One of our regular parishioners died as well. But I’m working in the community to encourage the people. I am not just working for the church, I’m working for the community.”

It was clear to me that the pastor genuinely cared for his community, Christian or otherwise. It was also good to see that there were others here who were remarkably selfless. A good example is Bishnu Maya Ranamagar, but for whom there would be no celebration today. The land the church stood on belongs to her. She had offered it for the church.

Himal Sagar Hingmang (left), one of the musicians, and Bishnu Maya Ranamagar, on whose land the church stands. Photo: Patrick Ward

“No one was here to help up reconstruct the old church,” she said. “So I offered this to the pastor. One day, God will give us a way to build more. I am praying for that. I am full of sorrow, but today I have God and I am happy.” Last year, Ramnamagar told me, they had celebrated Christmas in a proper church. “It was a beautiful building, lit up and decorated,” she said.

The parishioners were beginning to queue up for lunch. It was a meal of rice flakes, chicken and cauliflower and the congregation spread itself under a tarpaulin roof, or on the mounds of mud and grass that surrounded the church. The pastor gave out sweets to overjoyed children.

After lunch, there was more music. Children packed in to dance, and swing off the arms and shoulders of adults who dared to enter. Himal Sagar Hingmang, a music video producer, was one of those providing the entertainment.

“Everyone here has fought sorrow and sad feelings,” he said. “This is a very sorrowful year for the Nepalese people. I hope everything is okay next year and we have happier moments.”

Hingmang said he had lost his production company after the premises collapsed in the earthquake. Now he wanted to work with the pastor to produce music videos to tell the world about the quake and its impact. He said they just needed the money for a camera.

Christmas story main text 4

By mid-afternoon, the celebrations came to a close. It was early, but the tracks across the hills were unlit and many needed to leave soon. A woman with a basket on her back picked up the sweet wrappers that the children had left. Men dismantled the sound system. Children swept the floor and helped to roll up the ground sheet.

I was staying the night with Pokharel. As we made our way down a steep, dark track to his hamlet, I noticed scenes of devastation. The pastor pointed out a small patch. Before the earthquake, six houses had stood here. Now all that remained was rubble and two shacks.

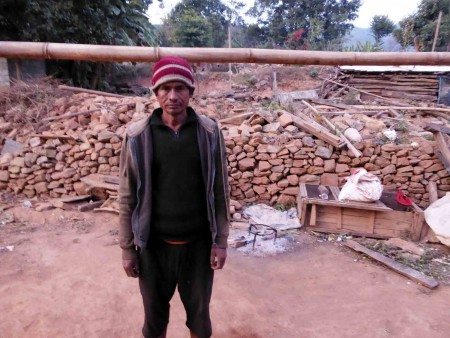

“Winter is so hard,” Sudarsan Khatri, who lived in one of the shacks. “This temporary home is no good. No insulation. It’s damp. We sleep at night and water drips on us.

Sudarsan Khatri. Photo: Patrick Ward

“We can’t rebuild because we don’t have the money. I don’t have much hope for the New Year.”

We couldn’t delay there too much. It was getting dark, and only mountain goats could work their way down this trail with any sense of ease. It took another 20 minutes of stumbling navigation before we emerged into a clearing, which housed several small shelters belonging to two families.

Pokharel’s shack appeared sturdy, with zinc sheets over a wooden frame. The main room doubled as the bedroom and living room and was kept as tidy as could be, considering the blurred boundary between the outside and indoors. It held three beds. Clothing hung from lines of strings tied across the rafters. There was an open kitchen area next to it.

The pastor shared the shack with his mother and his frail father, both of whom welcomed my intrusion with touching warmth, eager to share what they had with me, without reservation. Despite the language barrier, I was continuously corralled towards the warmest seat by the fire, invited to eat fresh-from-the-tree bananas, and handed metal cups of warm water to drink. The two words I heard frequently from Pokharel’s mother, which I did understand, were, “Hallelujah, dhanyavad!” [“Hallelujah, thank you!”].

Later, as night fell, we sat outside, under the giant leaves of a banana tree. Pokharel’s mother was cooking dinner outside. The pastor played Hindi songs on his mobile phone and we huddled there, around the open fire, against a backdrop of majestic hills and mountains, cloaked in mist and bathed in the light of a full moon. Yes, there was beauty, tranquillity, even amidst devastation.

Pokharel’s mother had prepared a traditional Nepali dinner for us—rice and potatoes with pickle—and we retired soon. I was given a bed to myself, and plied with warm blankets. I removed my thick coat; it was too much to sleep in. But I kept my woollen hat and gloves on and covered myself with blankets. It was still cold. The shelter had plenty of gaps through which the near-freezing Himalayan air drifted in. Pokharel’s father was sick, and the cold air could not be doing him any good. And there were hundreds, thousands, like him, caught in the cold, in the remote areas of the district. When would they receive the promised government help? Where did the NGOs go? Where will this family be next Christmas?

Many before me have written about the ‘resilience’ of the Nepali people, how they are brimming with it. Yes, there is resilience, but it is a resilience borne out of a lack of options. It is a reality that has been forced on them. It is, in essence, a question of survival. The only thing that appeared to be working for them, it seemed to me, was the way the community had rallied together. How people like Pokharel and Hingmang and Ramnanagar are doing what they can with the little they had.

“We don’t have the money,” Pokharel had said earlier. “But we have the heart.”

CREDITS

text, photo & video

Patrick Ward

video editing

Naomi Mihara

translation

Shrijana Baral

special thanks

Ram Hari

This project was facilitated by @GlobalBU, Bournemouth University’s global engagement hub. Versions of this story have also appeared in Huffington Post India and Rediff.com.