The day I arrived in Kathmandu, the Nepal government had just announced a quota system limiting the number of vehicles on the roads in response to the fuel crisis. Very few private vehicles were plying. Buses were completely packed. Taxis were charging three or four times the usual rate.

I had read about the protests taking place near the Indian border over Nepal’s new constitution even as I left England. I knew about the blockade of supply trucks at the border, and, in an abstract manner, about the fuel shortage that was beginning to grip the country. But I had little idea how much the situation was affecting everyday life across a country struggling to get on its feet after a devastating earthquake—and how angry, and upset, Nepalis were with their ‘Big Brother’ across the border.

“We are trying to put our house in order and a big neighbour has come to disturb it,” Dr Uddhab Pyakurel, a political sociologist at the Kathmandu University, was to tell me soon. “A small section of Nepali society has always been critical of India’s influence. But now, more people are feeling this way.”

India’s role in the fuel crisis has been extensively reported, and it would be difficult to find a Nepali who believes New Delhi’s claim that it was concern for the truck drivers’ safety that was behind the pile-up of supply vehicles at the border on the Indian side. Every person I spoke to in Kathmandu seemed to believe, perhaps with some justification, that India had effected an unofficial economic blockade to pressurise Nepal into editing certain provisions in its brand new constitution—specifically, those relating to the demands of the Madhesi people in the border region, with whom India shares strong cultural ties.

It is not surprising, then, that many in Kathmandu are fuming. The ordinary Nepali, says Anup Ojha, a journalist at the Kathmandu Post, feels betrayed. “We are feeling humiliated,” he said. “It shows that India can interfere in each and every part of our politics.”

It is not just the politics that people are upset about. The blockade has translated into everyday hardships for everyone here, to the point that some in Kathmandu feel it eclipses even the situation they faced after the earthquake. “This crisis is more troublesome than the earthquake,” said Munni Pandey, a mother I met in Pattan, on the outskirts of the capital city. With few taxis plying, Munni was frustrated at her inability to take her children to their schools on time; at home, she was about to run out of cooking gas.

Ramila (right) has run out of cooking gas and is no position to cook for her family of 12. Photo: Namita Rao

Kalyan Tamang, a bus driver who had been waiting in a fuel queue all morning, was more measured in his response. People were moving on from the adversities caused by the earthquake, he said, and trying to rebuild their lives. But the fuel shortage has hit them hard. Sangam Lama, a bus conductor, put it simply:

“If the buses don’t work, I don’t get my salary.”

A WEEK AFTER I reached Kathmandu, there were news reports that India had instructed its officials at the border to lift the undeclared blockade. The people I spoke to that day were cautiously optimistic that an end was in sight. “We are slightly relieved,” said Surya Dhungana, “but we cannot fully rely on that because we have been facing a similar situation for the past 30 years.”

Behind the negativity colouring that sentiment is the fact that the reprieve at the border is yet to alleviate the crisis in any tangible manner. Although trucks carrying fuel and other essential goods have begun to trickle in (or so I read in the newspapers), for the ordinary Nepali, nothing has really changed yet. The quota system is still in place for public transport and government-owned vehicles, which are allowed on the roads only on alternate days. Private vehicles received a slight relief when the ban on fuel sales was lifted for just one day. But in truth, the situation appears worse than it was, with the government now slashing the fuel quota for public vehicles.

Many in Kathmandu are also concerned about the upcoming Dashain, the biggest festival of the year, which lasts 15 days. There is a sizeable population in the city from other parts of the country, and traditionally, most people return home for the festival. But with the fuel rationing in place, transportation will be difficult to find.

For more than a week, schools have been running classes only on alternate days. Without fuel for generators, which are needed to tide over the prolonged power cuts caused by Nepal’s electricity shortage problem, businesses are seriously suffering. According to the Federation of Nepalese Chambers of Commerce and Industry, the cumulative effects of the two months of strikes, blockades and protests over the new constitution has cost the economy $1 billion.

Commuters travelling on bus roofs are a common sight in Kathmandu. Photo: Naomi Mihara

THE CRISIS HAS also severely disrupted earthquake relief work. Much of the cement, steel, glass and zinc sheets needed for reconstruction is imported from India. “These cannot be accessed by villagers unless there is a smooth transportation facility,” said Dr Pyakurel. “More than that, earthquake-affected villages need a large number of skilled and semi-skilled workers, many of whom come from the bordering cities of India. Given the situation, Indian workers may not feel safe to come to the hilly districts to carry out reconstruction.”

The biggest hindrance to relief work is, not surprisingly, the lack of mobility. “We are in a race against time,” said Iolanda Jaquemet of the World Food Programme, which has had to halt many of its operations because its delivery trucks are out of diesel. “Earthquake affected populations at high altitudes will be cut off from the world by snow in about 3-4 weeks.”

“It’s the same story for all NGOs,” said Ram Hari, who works for Mission East, a Danish NGO. His organisation faces the prospect of losing donor money because they would now not be able to finish distributing relief materials to meet a mid-October deadline. This also means that vulnerable families in Sindupalchok—the district worst-affected by the earthquake, where many are still living in tents—will not get the aid they have been promised.

Importantly, the issue that has spurred the blockade and fuel crisis still remains unresolved. Talks between the government and parties representing the Madhesis—the main group protesting their under-representation in the new constitution—are taking place, and the government has agreed to some amendments. But there is still much ground to be covered.

“In the Madhesh, there is palpable anger against Kathmandu,” said Daulat Jha, a Madhesi political analyst. “Right now, the polarisation is at its peak and will take time to decrease.”

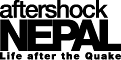

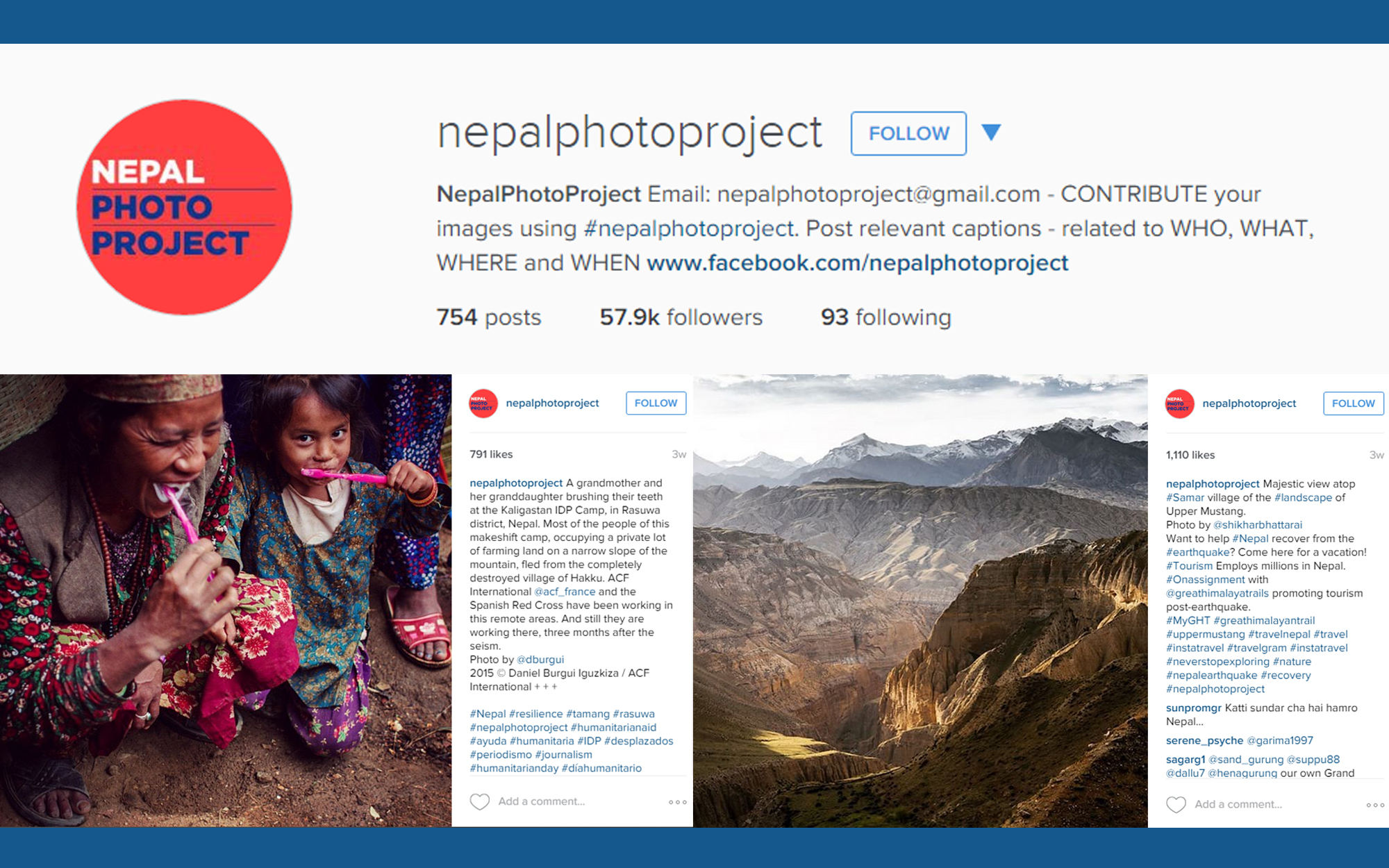

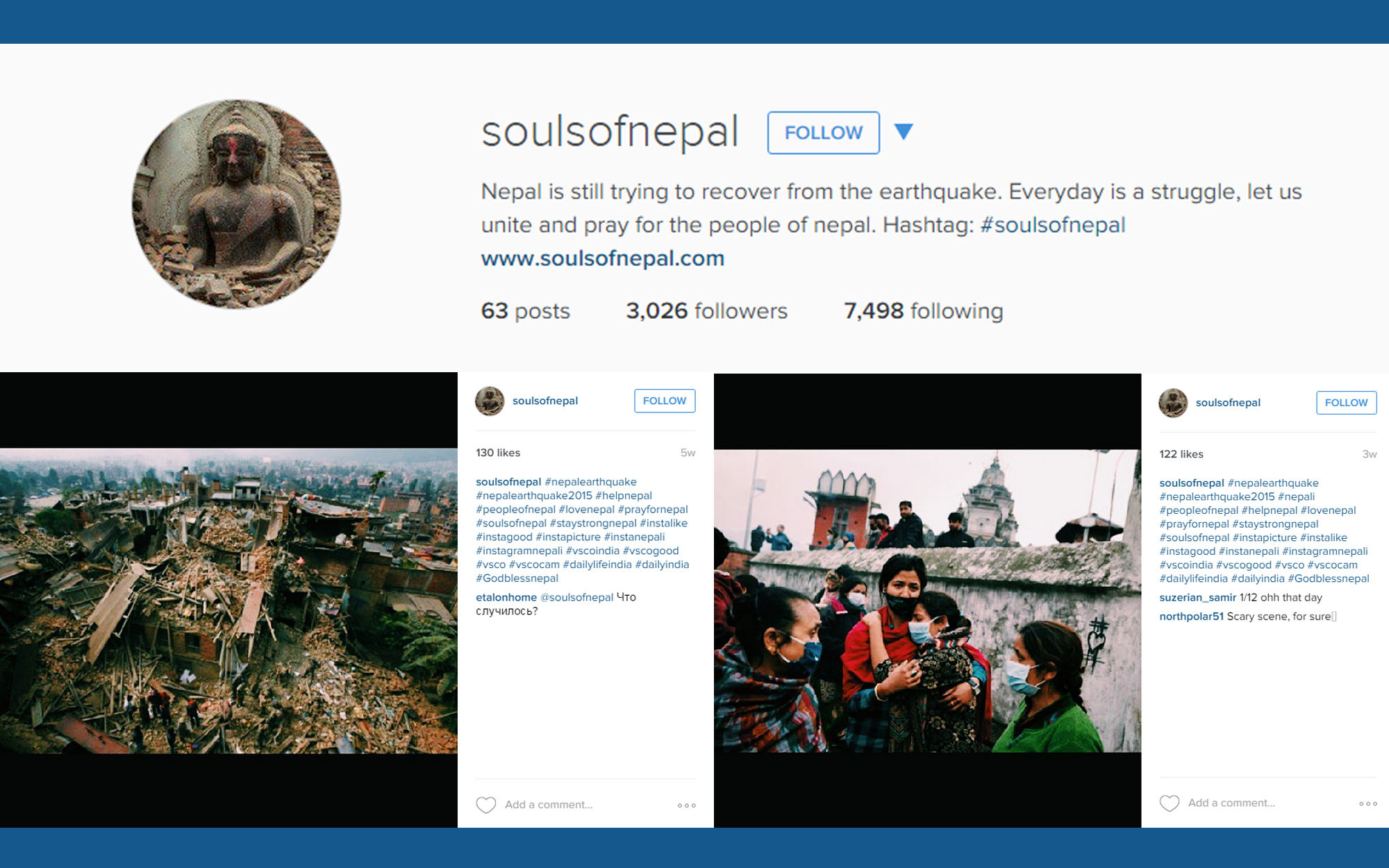

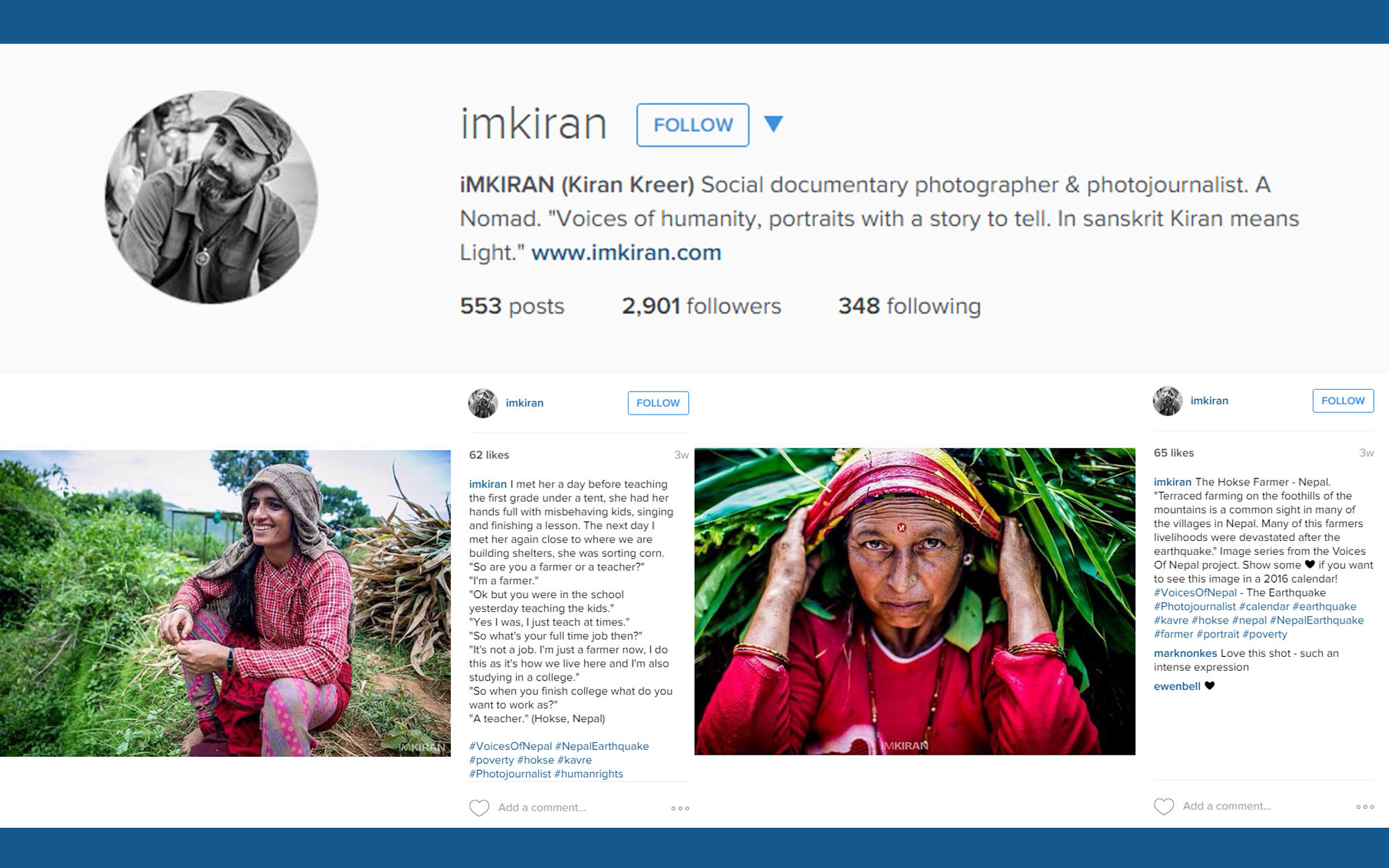

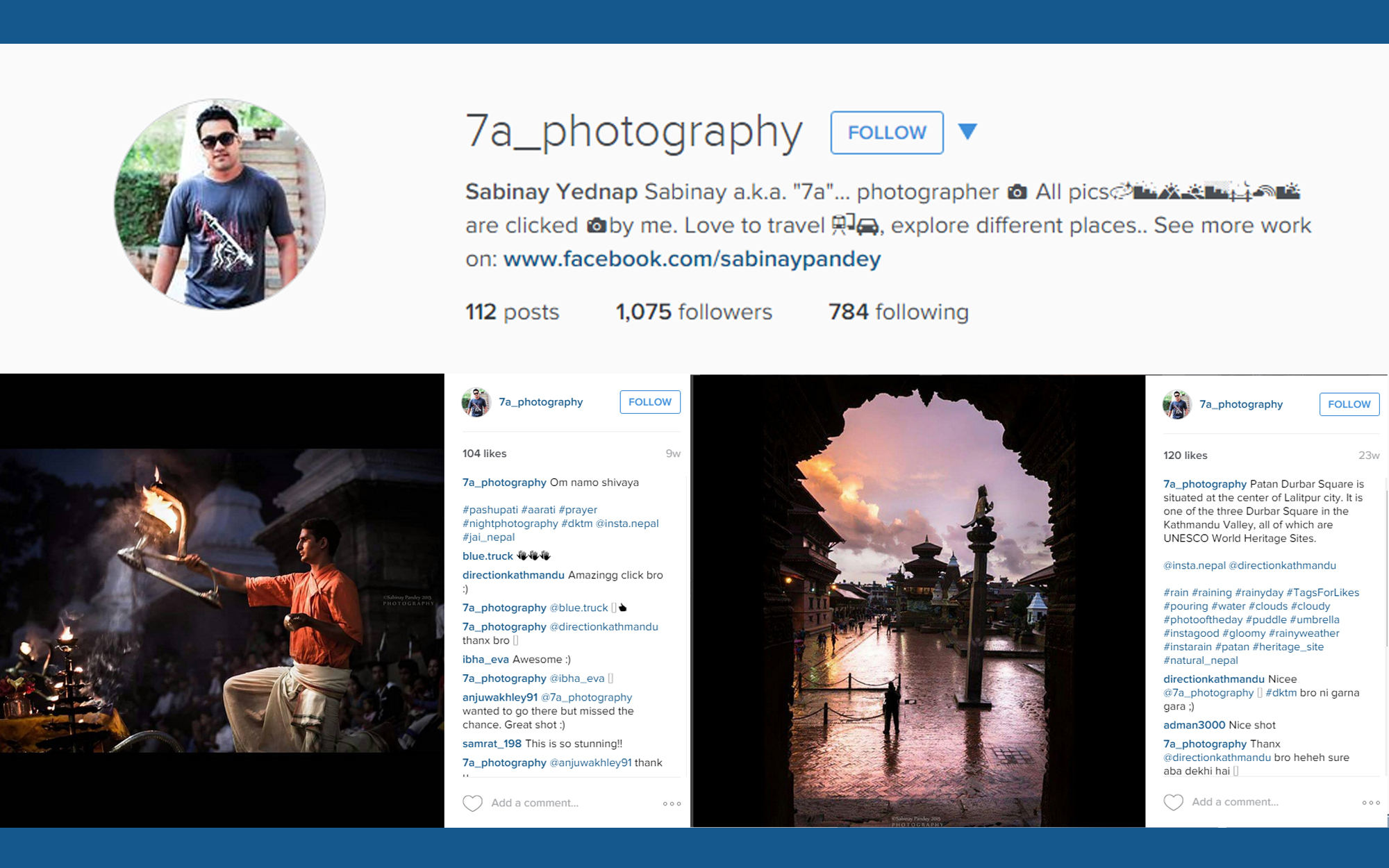

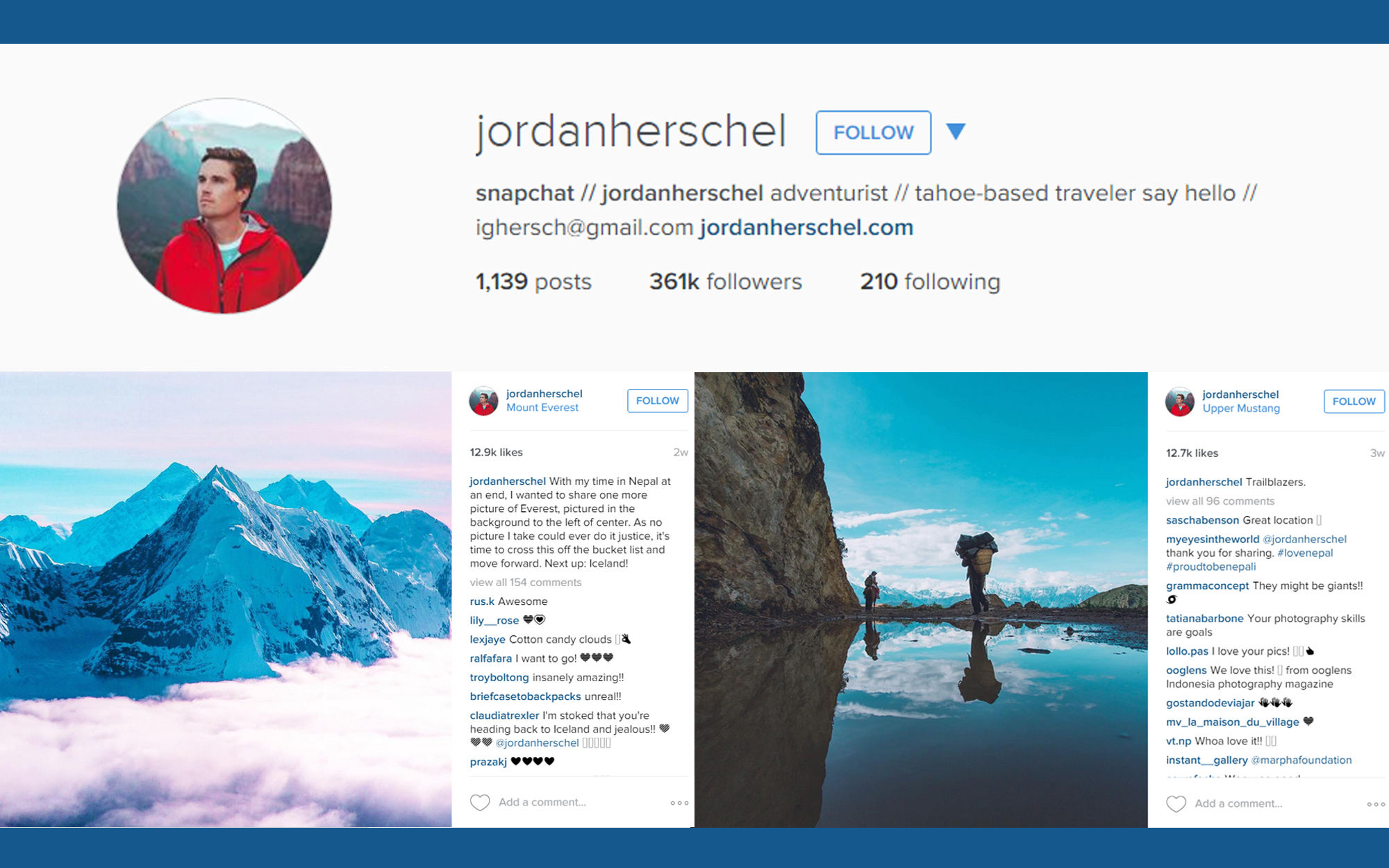

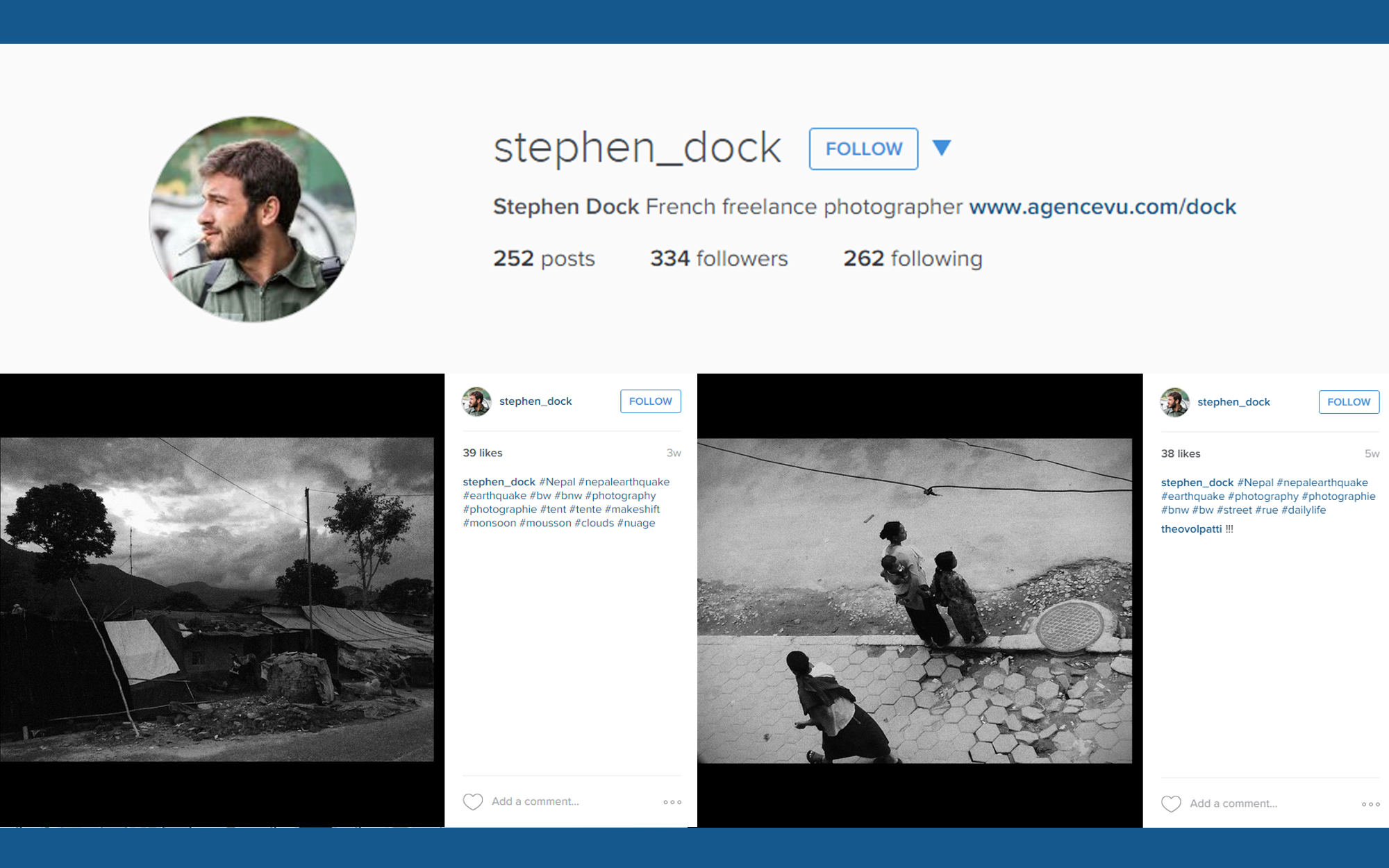

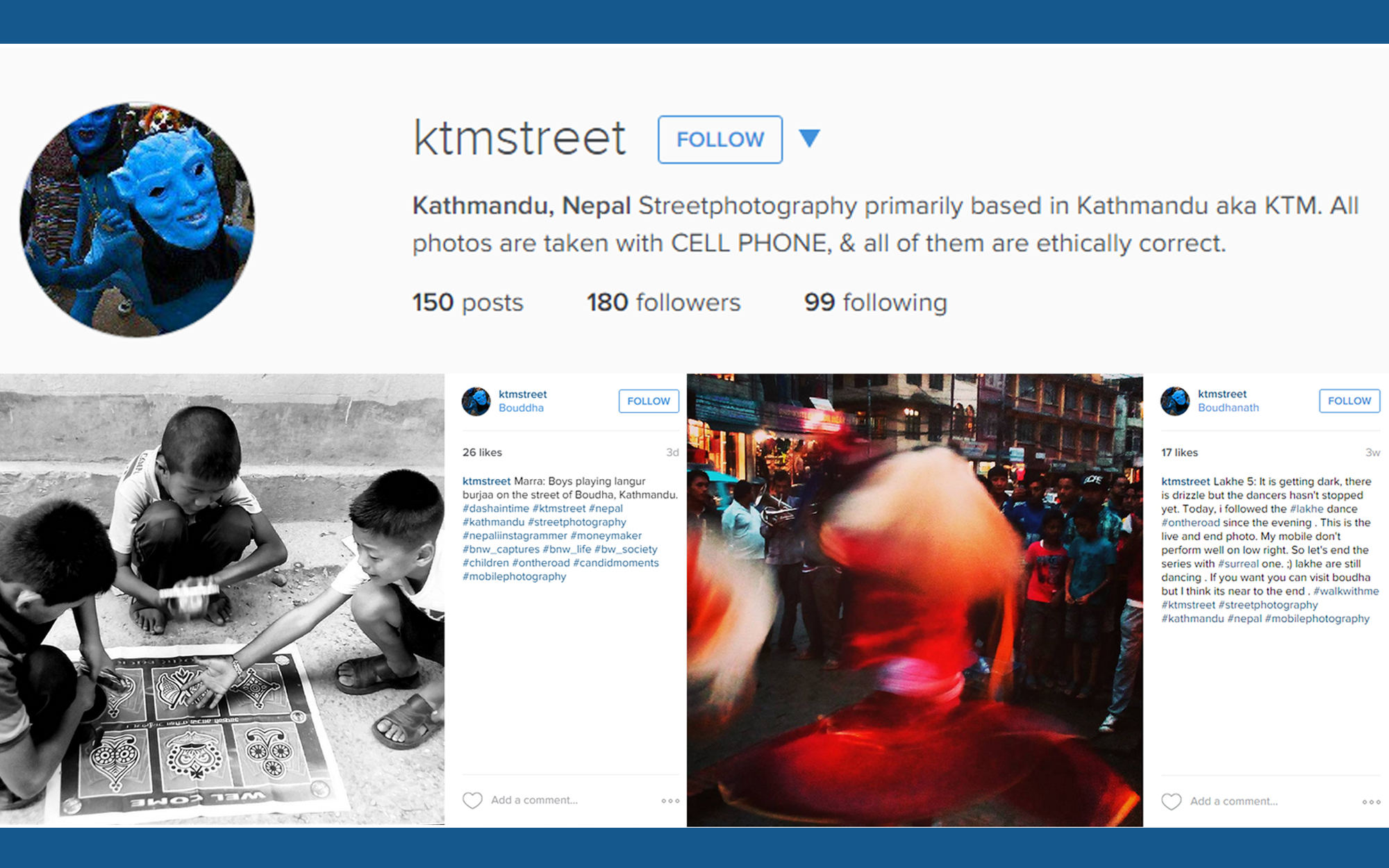

IN THE CAPITAL, though, there is much solidarity on display. People have grouped together on social media to voice their anger at India through hashtags such as #IndiaBlockadesNepal, #BackOffIndia and #DonateOilToIndianEmbassy. Residents have also resorted to sharing rides to get around. Carpool Kathmandu, a Facebook page to coordinate travel in and around the city, has now amassed more than 94,000 members.

“From one point of view, the situation has helped unite Nepalese people,” said Sagun Khanal, an accountant. “They are ready to help each other.”

Public buses queuing up at a petrol station in Patan last Thursday. Photo: Naomi Mihara

There is also a feeling that Nepal needs to rely less on India. As of now, more than 60 per cent of Nepal’s imports are from India and this over-reliance, many in Kathmandu say, makes their country vulnerable to manipulations. They point to 1989, when India imposed an official blockade that lasted 13 months, thought to be an attempt to punish Nepal for buying weapons from China. “Our situation is probably worse now than it was in the past, because we consume so many goods that are imported from India,” a Kathmandu resident said.

There have been calls for Nepal to reach out to other neighbours, especially China. The road to the northern Tatopani border point, buried by landslides after the earthquake, was hurriedly cleared and reopened last week. Last week, the government-owned Nepal Oil Corporation issued a tender for the import of petroleum products from any country through any medium, hoping to break more than 40 years of Indian monopoly as the sole supplier.

Besides the anti-India sentiments, many Nepalis appeared increasingly frustrated with their own politicians’ lack of action, foresight and ability to negotiate diplomatically. Following the promulgation of the constitution on September 20, Nepal’s parliament is attempting to form a new government. There is a sense that this has been prioritised over reaching a solution to the crisis.

“They have behaved very immaturely and disrespectfully,” said Dr Sudhamshu Dahal, an assistant professor at the Kathmandu University. “They should start putting people at the centre of their negotiations.”

Others are angry at Madhesi politicians and protest leaders for inciting unrest, rather than negotiating. “I understand that people in the Tarai are unhappy with the constitution,” a student said. “But this is affecting everyone’s lives.” There are also many who plead the cause for unity. In Ratna Park, a group protesting India’s actions held signs referring to the three regions of Nepal: “Himal [mountain], Pahad [hill], Tarai [plains]: no one is an outsider”.

Although anti-India sentiment in Nepal is high at this point, the India-Nepal relationship is not irreparably damaged. “Many people feel doubts about whether the kind of relationship that the two countries have had until now should continue,” said Dr Pyakurel. “Still, there is room to be engaged. But India needs to undo this blockage as soon as possible and allow Nepal to deal with its domestic problems on its own.”

Thankfully, the animosity felt towards the Indian nation does not seem to extend towards the Indian people. “We share a familiar culture, landscape, lifestyle… there are so many things that can bring Nepali and Indian people together,” said blogger Siromani Dhungana. “We have shared a special bond in the past, and I believe that will continue in the future.”

Additional reportage: Namita Rao, Ritu Panchal and Unnat Sapkota.